Fiji is well known for its rich array of traditional wooden artisanal products.

While menacing crafts such as clubs and the mighty sea-voyaging war canoes (drua) have enjoyed fame, the lali (wooden gong or drum), though an important part of life in old Fiji, seemed to have faded in prestige.

In ancient times, the lali was a communications tool that belonged to the community.

It summoned the early Fijians to important gatherings and warned them during an imminent attack.

The small hand-held lali were used as musical instruments during traditional dances known as meke while the huge ones measured up to several feet, depending on the seniority of the village chief who owned them.

According to Rod Ewins in the Domodomo article titled Drums of Fiji, the lali was more common in pre-contact times and was the specialty or iyau of “specific localities”.

The islands of Southern Lau in particular were famous for the variety of male and female wooden artifacts they fashioned.

These islands had an abundant supply of the coastal hardwood tree called vesi, which was used largely in the manufacture of wood crafts like war canoes, kava bowls called tanoa and lali.

Lali were commonly made from dilo, tavola and vesi timbers because they were dense and acoustically resonant.

Vesi thrived in limestone-rich islands, where the tree grew tall and wide around the trunk.

To fell and shape vesi, stone adzes, called matauvatu or isivi, which were strenuous to make and required regular sharpening, were the primary tools employed.

Ewins said the cutting of a new lali, because it was communally owned and important, was always a great event.

When a completed one was transported on a canoe to its intended destination, the lali was beaten all throughout the journey.

The lali’s specific beats told coastal villagers that it had just been completed and was being transported by sea to its owners.

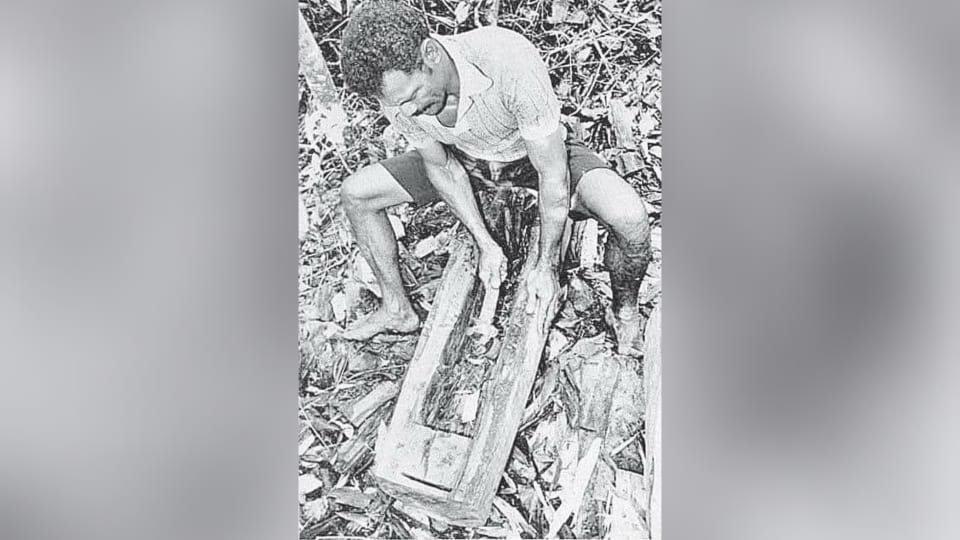

The making of a lali was a physically intensive job, requiring a lot of upper body strength and skills.

Once the preferred length of the lali was cut from the felled trunk, it was slowly given form and shape.

The rough shaping of the log was done in the forest using the felling axe called valevatu.

Ewins said firstly, the side of the log that would form the top of the lali (ketena) was chopped along its length with the axe, and then adzed flat with the valevatu through a process called cici kete.

The outsides were then fashioned through a shaping action (umani) before the hollow interior (loma ni lali) was strongly chopped out (tuki dreke).

When the basic form of the lali had been decided and the weight of the log reduced, by the emptying of the sides and the interior, it was then carried back to the woodsman’s home using two poles called ivua to be completed by fine “chiselling” and detailed handiwork.

Sometimes taking the crude body of the lali to the village took a few miles of walking on foot through thick jungle and mountainous terrain. Finishing of the cavity was done using the tools, tabu magimagi and the calocalo.

The sides and underparts of the “belly’ (dago ni lali) was adzed to a sound shape and reasonable finish.

It was common practice to carefully place the finished lali inside the bachelor’s quarters known as valenisa or burenisa.

It was only brought out for beating during special occasions or to signal special events. Ewins said while in modern times the lali was merely used to tell the time in schools and in churches, it had many more uses in the past.

He said the lali and its beats differed according to their significance. They were meaningless to strangers but were easily recognised by those who heard them and understood their message.

“Even in living memory, lali could not be beaten casually….”

In history literature, more reference is made to the bamboo instrument called derua than to the rugged looking lali.

The beating of the derua tubes signalled that the corpses of bokola killed in battle were being carried into the village ready for communal ritualistic feasting.

Describing the beating that accompanied the bokola’s arrival, Reverend Thomas Williams wrote this in Fiji and the Fijians: “When the bodies of enemies are procured for the oven, the event is published by a peculiar beating of the drum…”

Some of the lali beats that were used in the olden days included the vakataratara, lali in tabua, lali ni waqa, lali ni kabakoro, lali ni bokola, lali ni bure kalou and lali ni sautu.

Ewins said the vakataratara was for raising the tabu, four nights after a chief’s death while the lali ni tabua (beaten on two drums, the first called kaba bu) was sounded when receiving a tabua or in times of stress or

war.

The lali ni kabakoro was beaten when besieging a village while in very formal warfare (ivalu votu) a big wooden lali was beaten to warn the defenders when they were likely to be attacked. The number of beats at the end showed the number of days left before the planned attack.

During a siege, the lali was beaten non-stop when signalling for help from “friends” and allies.

The lali ni bokola was beaten from behind the ramparts of a fortified village, within the field or on board a canoe.

“It was beaten to proclaim the capture of enemy bodies and the start of the victory dance over them prior to their sacrifice and cooking,” Ewins said.

The victory dances were, the cibi for men and the dele or wate for women, the latter performed with a sexual theme and stimulating vigour which Ewins said were an “extraordinarily lascivious affair”.

Due to the fact that the lali had a signifi cant communications role to play during battle or surprise attacks, it was a prized “spoil of war”.

In the book The Hill Tribes of Fiji, colonial administrator Adolph Brewster wrote that during one of Ratu Seru Cakobau’s victories in the 1870s, the Bauan chief’s spoils of war included “the great big wooden lali or war drums…”.

The sacred lali ni burekalou was beaten at the village temple site, lali ni sautu was sounded to signify a truce reached in battle and lali ni vutu was beaten at the birth of a chief.

The lali ni meke or dance drums were the most popular wood crafts for pastime in Fiji and signifi ed peace times and celebrations. It provided music for the chant that were sung and was accompanied by the sticks and derua.

Lali ni meke are similar in shape to the large drums, only they are typically smaller (30 to 60 centimetres long). They are used during entertainment segments or adored during special celebratory events and traditional gatherings.

“The sound they emit when struck with their little beaters is sharp and piercing but not resonant,” Ewins noted.

Today, the huge war drums are no more, its prominence usurped by the slightly smaller ones beaten in villages to summon people to church or for telling the time in rural schools where there are no bells or sirens.

Some experts say the lali is neither a drum (because it has an open hollow), nor a gong because it is does not have fl at plates. Ewins said it could even be a type of wooden bell.

Whatever it is technically, the lali showcases the superb craftsmanship of old traditional woodsmen, who created wood artifacts that survived the ages and are still capable of “making noises” in 21st century Fiji.

(This article was compiled using information from the article Drums of Fiji by Rod Ewins published in the Fiji Museum quarterly magazine, Domodomo Volume 4, 1986)

- History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be thesame as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.