The German philosopher, Theodor Adorno, once remarked that one of the most unintelligible ways of making a point is by simply splashing around in what he called ‘your own linguistic cascade’.

What we need to do, instead, is to reflect on the words we are saying or need to say, paying particular attention to contexts in which we are uttering them.

This observation was brought forcefully to us as we read that our Prime Minister made the rather dim point, in an iTaukei Affairs-sponsored television program on Fiji One, that the Great Council of Chiefs (GCC) was created by the colonial establishment for the sole purpose of ruling and weakening the commoners.

This kind of utterance can only come about when we judge history through lenses that have been imbued with present-day values or other political agendas.

It is a truism in historical circles that this is not how history has to be understood.

The GCC, as the historians would gingerly put it, is a ‘child’ of its times. It did not exist in a vacuum. It was there together with the native ordinances, the native register or Vola ni Kawa Bula and the tribal statements (Tukutuku Raraba) as part of the colonial attempt to bring order and stability to a rather chaotic iTaukei environment that they were confronted with.

Together, these legal documents created a common iTaukei identity that is still vibrant today.

As you will have gathered by now, this is one of the pillars of the ‘divide and rule’ policy in colonial Fiji; a strategy of willfully separating Indians and the native population in an effort to consolidate colonial rule and the legitimacy of the (small number of) white settlers in Fiji.

The native ordinances were there to ensure that the iTaukei population was adhering to regulations that, in the view of the colonial establishment, would ‘civilise’ them.

These ranged from matters of hygiene and clean living in the villages, the sizes of dalo plantations every adult must have, to what kind of people can actually go to urban areas.

The cumulative effect of these ordinances was that native life became highly regimented as communities became, in effect, ‘disciplinary regimes’.

The native register (Vola ni Kawa Bula) was a compilation of the members of the different tribes and clans that make up the landowning units in all of Fiji. It was also a record of who was a legitimate landowner and who was not within a landowning unit.

The distinction here is between children born in and out of wedlock. Needless to say, this has ramification for leadership claims within a landowning unit. The tribal statements (Tukutuku Raraba) are an ‘agreed’ account by members of a tribe of the origins of clans within it.

They also depict the roles of the different clans in relation to the tribe. T

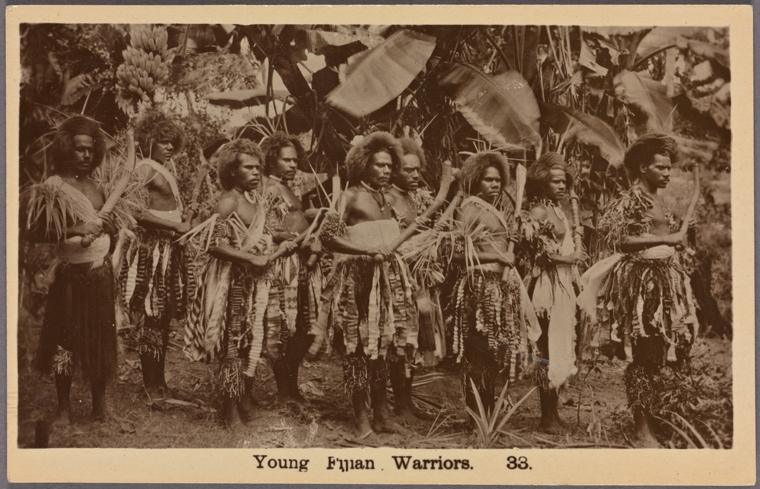

hese roles are classified in the tribal statements as sacred-chiefs/chiefs (sauturaga/turaga), heralds (matanivanua), warriors (bati), carpenters (mataisau) or gonedau (fishermen)). Furthermore, they also depict the relations between different tribes in a vanua in those roles defined above.

For instance, one may be chief in a tribe that is known as the traditional fishermen of another tribe.

Multiple identities

So the iTaukei people naturally find themselves navigating multiple identities related to their functional roles as they go from their own clan to their tribe or from that tribe to another related tribe within the vanua.

Vanua relationships, in the main, are arranged in a similar fashion. Taken together, the native register and the tribal statements became the defining document of who is who in the iTaukei population today. Accordingly, iTaukei identity became associated with a particular village, specific clans, tribes and vanua. Every iTaukei is supposed to know, in other words, his or her village, communal land holdings, traditional role and vanua.

The institutions that were set up to enforce and perpetuate these practices were the now defunct GCC (Bose Levu Vakaturaga) and the Native Lands Commission (Vale ni volavola ni Veitarogivanua), now the iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission.

One of the things that strike us from the various designations of the iTaukei above is that the term ‘commoner’ is really nonsensical when viewed in its proper iTaukei context.

Who are the commoners in the iTaukei community? Are they the sauturaga (sacred chiefs) or the matanivanua (chiefl y heralds)?

Or are they the mataisau (communal craftsmen) or gonedau (communal fishermen)? Are commoners equated with the bati (warriors)?

It simply does not make any sense to refer to these groups as commoners when chiefly installations are subject to their presence.

The word ‘commoner’ is more understandable in its English usage where there is an emotional distance between the aristocrats and their subjects. The subjects in this (European) context play a more spectator role in the making of a traditional leader.

One can see this in coronation ceremonies where commoners are distinguished by their trivial role as bystanders in a ritual that is dictated mainly by religion-feudal absolutism.

In contrast to the European context above, there are no real ‘commoners’ in the iTaukei setting. For instance, the chief is only a chief as long as the different clans and tribes in a community are willingly playing their respective roles in the service of the vanua.

Chiefl y installations are, in this way, sacred pacts between the different tribes in a Vanua and the person that has been selected to lead them. The words uttered in those ageold rituals speak of the mana of the vanua being transferred from the people to the chief so that he or she may lead the vanua in a way that is conducive to the well-being of all.

Failure to heed the voices of the people leads to the loss of mana in a chief.

This puts paid to the notion that one may safely understand and use distinctions derived within a feudal context in Great Britain to the iTaukei understanding of vanua. They are as different as chalk is from cheese.

Yet judging from the PM’s recent pronouncements, he seems to be not fully aware of the differences above. In fact, his verbal sleight-of-hand, casting the GCC as a colonial construct with the aim of empowering the rule of the ‘chiefs’ at the expense of the ‘commoners’ is one straight out of a European storybook.

Better leaders

To be fair, the PM has, in the past, pointed out that the existence of chiefs is not conditional on the existence of the GCC. Be that as it may, it is another thing altogether to start making distinctions between the chiefs and the people (who play an active role in the making of their leaders) as one that is detrimental to the latter.

An understanding of our societal trajectory shows that Mr Bainimarama may be referring explicitly to the post-independence politics surrounding the GCC. The discourse on chiefs and vanua has highlighted this defunct body to a bedrock of ethno-nationalism in a country like ours.

The GCC has been implicated in the coups of 1987 and 2000. The hypocrisy in that institution came to light in the debacle surrounding the negotiations between the coup-makers and the GCC in the aftermath of the 2000 coup.

However, it is our view that this is not a reflection of the institution itself but the power complexes of some chiefs who had sway in that establishment at that particular moment in time.

They were power-hungry men who abused the trust of their vanua. Instead of trying to be leaders offering a better vision for all Fijians at a critical point in time, they became entangled in a game of power-play for their own benefi t. Their agenda was always parochial.

Does this mean, as the Prime Minister suggested, that the GCC is a tool of oppression?

We believe that the usage of the GCC by Mr Bainimarama is a red herring. By splashing around in his own verbiage, the PM is doing nothing imaginative but creating a political wrinkle.

His hope is that this will drive a wedge between the so called ‘chiefs’ and ‘commoners’ within the iTaukei population. It is simply a political ploy to charm the young and impressionable.

And chiefs? What about them?

First, if we are to have chiefs in our midst as we go forward as a multi-racial country then we need a new breed of visionary leaders.

The future of our country depends on this. Of course, there have been indications that our chiefs can be movers and shakers in the national arena. One has to look no further than Ro Teimumu Kepa and her vanua of Burebasaga to realise this.

Her (and her people’s) magnanimous act of generosity in accepting the descendants of the Girmitiya into her vanua sets her apart from her contemporary peers.

The brilliance and broad-mindedness of the late Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi is another case in point. What we need are more chiefs like these two.

This is to say that we need leaders who can clearly grasp clearly the links and tensions between their parochial duties and their national obligations – leaders whose sights are firmly fixed, with other community leaders, on a shared future, however that may look. It is up to rest of us to take our cues from them.

The GCC, once touted as the bane of Indo-Fijian security and aspirations in Fiji, is now being rehashed in the public realm by the government as a threat to iTaukei sensibilities.

By willfully forgetting what the GCC really means to the iTaukei people in Fiji, this government, in our view, is becoming an existential threat to the vanua itself.

- Dr TUI RAKUITA teaches at the School of Pacific Arts, Culture and Education. SEVANAIA SAKAI teaches at the School of Law and Social Sciences. The views expressed are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the views of this newspaper or USP.